Saturday, December 14, 2013

Inventing a Religion...or Not

Sunday, December 1, 2013

The Lord Chamberlain Lives!

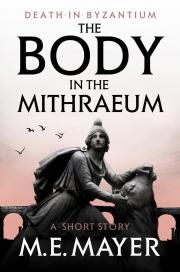

Our writing has more energy than I do right now. It's still getting out and about. For example, the second ever John the Lord Chamberlain story is now available as an ebook from Head of Zeus. Under the title A Mithraic Mystery it appeared in 1995 in The Mammoth Collection of Historical Whodunnits and Historical Detectives. Our first Byzantine mystery (A Byzantine Mystery!) was a very short puzzle oriented story in which the the Lord Chamberlain was little more than a cypher, and honestly, not much like our subsequent sleuth. (We think it was malicious gossip passed on by Procopios) When editor Mike Ashley asked us for a second tale about John we decided to start fleshing the character out. For the Head of Zeus reissue we did extensive rewriting and we hope it can serve as a short intro to the series under the new title:

Our writing has more energy than I do right now. It's still getting out and about. For example, the second ever John the Lord Chamberlain story is now available as an ebook from Head of Zeus. Under the title A Mithraic Mystery it appeared in 1995 in The Mammoth Collection of Historical Whodunnits and Historical Detectives. Our first Byzantine mystery (A Byzantine Mystery!) was a very short puzzle oriented story in which the the Lord Chamberlain was little more than a cypher, and honestly, not much like our subsequent sleuth. (We think it was malicious gossip passed on by Procopios) When editor Mike Ashley asked us for a second tale about John we decided to start fleshing the character out. For the Head of Zeus reissue we did extensive rewriting and we hope it can serve as a short intro to the series under the new title:

The Body in the Mithraeum

Byzantium AD 533: In a secret underground temple, the victim was blindfolded, bound with entrails and cut open with knife. In blood, a scrawled message: 'thus perish all who hate the Lord of Light'. Who could have performed such an abomination? Why has the Empress Theodora taken such a personal interest? John's investigation will lead him into world of hidden cults and lethal palace secrets.

The Body in the Mithraeum at Head of Zeus.

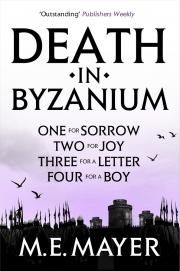

For a much longer intro you can now purchase the first four novels of the series in an e-book "boxed set":

For a much longer intro you can now purchase the first four novels of the series in an e-book "boxed set":

NOTE: We have suggested they might correct the spelling on the cover image!! Consider this .jpg a collector's item.

ONE FOR SORROW: When the body of a high-ranking treasury official is found in a filthy alley, John's investigation stirs the ghosts of his past and threatens his life.

TWO FOR JOY: John must discover why three of Constantinople's holy stylites have burned to death atop their pillars.

THREE FOR A LETTER: The murder of a child threatens Justinian's dreams of resurrecting the glory of Roman Empire. John will need all his wits to keep his job... and his head.

FOUR FOR A BOY: In this series prequel, John the slave takes his first steps along the dangerous path that will lead him to become Justinian's Lord Chamberlain.

DEATH IN BYZANTIUM: At the heart of what is left of the Roman Empire, lies a city simmering with intrigue & treachery. Amid this maelstrom stands John, ex-slave, now the right hand of Emperor Justinian. It is John's skills as an investigator that Justinian prizes the most. But the emperor is not a sentimental man. Nor is he a patient one. John knows his position is precarious. One misstep and his enemies may have him. And if they don't, the emperor himself almost certainly will.

Lastly, Poisoned Pen Press will be publishing Ten for Dying in March, but more about that later.

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

Review: The Secret House by Edgar Wallace

As is usual with Wallace's works, The Secret House gallops off to a cracking good start with a seedy fellow being interviewed for a job as assistant to the editor of a scandal rag called The Gossip's Corner -- an editor whose face is concealed during the interview by a bag-like fine silk veil tied under his chin. That would give most people pause, but the applicant takes it in his stride and gets the job.

Not long afterwards a millionaire named Farrington overhears two men arguing virtually on his doorstep about turning in the notorious blackmailer Montague Fallock, a man of whom there is no known photograph. Suddenly two shots are heard and both men lie dead.

Naturally when the police arrive Farrington's house is searched. Assistant commissioner T. B. Smith of Scotland Yard (who happens to live in the same London square) discovers the millionaire's area door is ajar. Not only that but he also picks up a gold scent bottle with the same perfume he detected in Farrington's hall although it is not that used by Doris Gray, Farrington's niece and ward. The only other clue is a silver locket engraved with a couple of lines whose meaning is unfathomable, discovered on one of the dead men.

Among other characters the reader meets Frank Doughton, who loves Doris, adventurer Count Paltavo, Doughton's rival for her affections, Lady Constance Dex, friend to Farrington and Doris, and Dr Fall, physician to Mr Jim Moole. Mr Moole is the never seen eccentric owner of The Secret House in the village of Great Bradley, and many are the stories told about him.

My verdict: The plot is a rich stew of sinister foreigners, fraud, murder, the search for a missing heir, a most peculiar will left by a suicide, disappearances, rooms that change in the twinkling of the proverbial eye, revenge, and much more besides. While some elements are far-fetched, still it's one of those yarns carrying the reader along at a breakneck pace until an unusual denouement putting Smith in danger of...well, better not say, but as a hint alert the reader to consider the estate on which stands The Secret House.

Saturday, November 9, 2013

FIRE-TONGUE BY SAX ROHMER (REVIEW)

If only Sir Charles Abingdon had confided in Paul Harley right away instead of deciding to reveal the full extent of his fears over dinner the following evening...but he didn't and is just about to tell all when he dies at the dinner table. Sir Charles' last words are "Fire-Tongue...Nicol Brinn...."

Nicol Brinn is easy enough to find, being a world-famous daredevil hunter and explorer who's been courting death for years in all parts of the globe, but when Harvey mentions Fire-Tongue he is obviously shaken to his core. Yet he too refuses, for the moment at least, to reveal what he knows of Fire-Tongue. Meantime, Harvey meets and falls for Sir Charles' daughter Phyllis and is not thrilled to hear the effete, hyacinth-loving Persian Ormuz Khan is paying her too much attention, or at least according to views held by British gentlemen on what constitutes proper conduct. It's up to Harvey and Brinn, working with Inspector Wessex and his colleagues, to deduce the mysterious entity's identity and thwart whatever devilish plans he or she is doubtless hatching.

My verdict: Fire-Tongue is curiously subdued for Rohmer. Its solution depends more on deduction and investigation than on fisticuffs, although a chilling chase along a deserted country road and the usual derring-do in an isolated mansion do feature. Part of the back story strays into classic Rohmer territory, which is to say it is more than somewhat far fetched, but here it explains a great deal about a pivotal character. Not a bad read for an idle evening.

Etext: Fire-Tongue

Friday, August 23, 2013

Ronald Standish by Sapper (A Review)

Narrated by Bob Miller, this collection of short stories involves his friend Ronald Standish. Wealthy and something of a sportsman -- particularly keen on golf and cricket -- Standish only takes cases that interest him and having done so persists until he solves them or, according to Miller and unusually for amateur detectives, must own himself beaten. His greatest assets when investigations are afoot are an excellent memory for faces and unusual facts and a talent for noticing small details others have missed.

In this entertaining work, Miller relates several investigations undertaken by Standish.

THE CREAKING DOOR tells what it knows and thus aids the discovery of the culprit when an artist is murdered after a scene precipitated by his kissing a girl against her will. The story ends with a rather nasty twist.

THE MISSING CHAUFFEUR works for the Duke of Dorset and has done a bunk the week before Grand Duke Sergius of Russia is due to stay for a few days. A letter written in blood arrives...

Visiting the small Cornish town of St Porodoc,, Standish and Miller hear a strange tale from a young curate who sees a ghost in THE HAUNTED RECTORY. A garden snail points to the solution of the mystery.

Love's young dream is thwarted by lack of cash, and when a valuable tiara is stolen only the suspect's beloved believes him innocent. It takes A MATTER OF TAR to show who was really responsible for the theft and associated assault.

The sister of one of Standish's fellow cricket-players consults the detective about her new neighbour, who runs a boarding kennel but mistakes an Irish terrier for an Airedale -- and reacts with fury when corrected. And whose is the terrified face seen peering from a window of THE HOUSE WITH THE KENNELS?

Standish is consulted about a letter his client's uncle received instructing certain papers be left in a specified place. Not long afterwards the uncle fell to his death, his son came into the estate, is sent an identical communication, and in turns dies. What will THE THIRD MESSAGE say?

It takes Standish some thought to solve THE MYSTERY OF THE SLIP COACH, wherein a man is found shot to death on a train with a smashed egg splashed about his compartment in a nice example of the locked room mystery.

An extremely unpopular village resident is found murdered and nobody mourns him. It looks bad for the man with more than one reason for a grudge against the departed. THE SECOND DOG provides the clue clinching the solution to a case of revenge....

Threats from Indian priests over disrespectful behaviour toward temple dancing girls follow a man who has returned to England and who now fears for the safety of his niece at the hands of THE MAN IN YELLOW seen flitting about the house and yet never found.

A blackmailing cur is brought to book by THE MAN WITH SAMPLES in a story getting my vote for the best in the collection, not least because of the method used to catch him, which neatly sidesteps a situation in which as is usual with blackmail his victims are very reluctant to involve the police.

When a retired businessman purchases THE EMPTY HOUSE and arranges for its renovation, incidents of vandalism begin and he receives warnings he will regret taking up residence, escalating in an attempt to run him down. Yet what could be the reason?

An obnoxious landowner is found drowned in THE TIDAL RIVER and a young man is brought to trial on charges of murdering him in what appears to be an open and shut case. But Standish casts his line out for other fish..

My verdict: An enjoyable read presenting challenges of various degrees to those who enjoy trying to guess whodunnit. Standish is more of a cerebral detective than a scientific sleuth, which will add interest for those who like their crimes solved without bubbling test tubes or advanced electrical whatnots getting involved.

Sunday, June 16, 2013

Stick Figures to Schiele

STICK FIGURES TO SCHIELE

One of the great things about the Internet is the amount of artwork on display. I could never afford coffee table books full of reproductions and rarely had the opportunity to visit museums or galleries, but today, thanks to endless web galleries, my computer desktop displays a rotating art show featuring paintings by Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth, Pierre Bonnard, Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt, and many more. Yes, I admit that I even have some non-classical works such as Weird Tales covers by Margaret Brundage.

One of the great things about the Internet is the amount of artwork on display. I could never afford coffee table books full of reproductions and rarely had the opportunity to visit museums or galleries, but today, thanks to endless web galleries, my computer desktop displays a rotating art show featuring paintings by Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth, Pierre Bonnard, Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt, and many more. Yes, I admit that I even have some non-classical works such as Weird Tales covers by Margaret Brundage.

My taste in art, like my taste in literature, is rather conservative -- some might say backward looking. I prefer figurative to abstract. I like impressionism. I enjoy the realistic tour de forces of Alma-Tadema and other Victorians. The work of the Pre-Raphaelites fascinates me. I prefer a picture that tells a story, which is probably why I never aspired to be an artist.

Not that I haven't dabbled in art. I was always well supplied with paper and crayons, not to mention pencils, pens, paints, pastels, and charcoal. As a kid I spent almost as much time drawing as playing in the backyard. Often my friend from next door would come over and instead of re-enacting the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral again we'd sit on my grandparents' porch and draw endless cartoon stories -- featuring plenty of guns and bombs -- on the rolls of adding machine paper my grandfather brought home from work. Those stories would keep getting longer and more exciting and violent until the long strips of uncoiling adventures began to flap in the passing breezes.

I had drawn stories long before I learned the alphabet. When I became proficient at writing I added captions to my drawings or word balloons. Instead of learning the multiplication tables I'd sit in the back of the classroom and draw cartoons for my buddies, including plenty of guns and bombs.

There were periods in my youth when I thought I might be an artist but I was never much good at drawing, nor was I inclined to work at it very hard. I have always liked drawing birds because they don't have those dreadfully complicated hands (now let's see, looking at the hand like that, which side should the thumb be on?) or even mouths to get wrong. For a couple of years I produced stick figure "mini-comics'. (More than twenty-five years ago -- long before XKCD -- amateur comics enthusiasts were employing stick figures, which allowed even those who couldn't draw to make comics.)

I came to realize that I was not interested in visual art for itself but only as a means to say things that were better -- and in my case more easily -- expressed in words. I was better served practicing my writing rather than my drawing.

There is a lot written about the "meaning" of books and paintings and other art forms, as if the works themselves are a sort of complicated shell within which the artist has concealed what he wants to express in such a way that it needs to be winkled out by experts. But if the purpose of a novel or a painting was to say something that could be said in a paragraph then the author would have written that paragraph instead of the novel and the painter would have placed himself in front of a keyboard rather than an easel.

Paintings are in large part about what we see -- form, color, light. Just as music is about sound. Writing about a painting in words gives the impression that the painting is about something that could have been expressed in words, which is misleading. Abstract paintings are purely visual, which is probably why I prefer paintings with some lingering attachment to real objects. In a Hopper I can find a bit of the literal element -- the story -- that attracts me, to go along with the visual. I cannot enjoy a visual experience much when it is entirely unhinged from any literal interpretation.

I have read psychological analyses of Hopper's works, often stressing the sense of loneliness and isolation, and while there is likely some truth to this I suspect Hopper was much more concerned with shapes and light, even in those paintings which feature human figures.

Probably I project more literal meaning onto the works of Hopper and other figurative painters than they intended. That's because I am literal minded. I am story oriented. Had I chosen to pursue art I could only have been an illustrator and the role of the illustrator is diminished in these days of cameras and computers anyway. Deciding to write was a good choice. But I think that my artistic upbringing and inclinations sometimes help me visualize the sixth century world Mary and I write about. Or at least I hope so.

Saturday, May 18, 2013

A Lone Daffodil

On the Poisoned Pen Press blog, for the last month of spring, Mary reminisces about A Lone Daffodil.

Monday, May 13, 2013

Those Brilliant Debut Authors

I'm not very familiar with the work of Dean Koontz but Mary has been on a bit of a Koontz kick which convinced me to give him a try. I thoroughly enjoyed The Taking, a very very creepy science fiction with an end-of-the-world scenario.

Koontz must have improved vastly because his early sf, as far as I can remember (I seem to recall something in Fantastic) was barely memorable. Well, aside from Invasion.

I reread Invasion after I read The Taking. It impressed me back in the seventies and it held up pretty well. It's a tautly written account of a family, trapped by a snowstorm in an isolated farmhouse, being menaced by alien invaders. (The situation is either trite or classic -- take your pick) Not only did I enjoy Invasion, but it probably scored extra points for being a Laser book that was actually good. You might recall that Harlequin's attempt to manufacture a line of crank-em-out science titles in the mold of their Romances didn't pan out very well from either a financial or (IMHO) artistic standpoint.

However, when I first read Invasion I thought I was reading a book by a promising new author named Aaron Wolfe.. What else would I have thought, given Laser editor Barry Malzberg's disingenuous introduction:

"This is Aaron Wolfe's first novel. Thirty-four years old and successful in another artistic field he has asked for compelling personal reasons that his real identity not interfere with his fiction and therefore "Aaron Wolfe" is a pseudonym. He is thirty-four years old, married with one child and lives in the midwestern United States.I realize that authors employ pseudonyms with various degrees of transparency for many reasons. As often as not pseudonyms are used to avoid confusing readers when a writer puts out books of different sorts or in different genres. Today it is often necessary to adopt a new literary identity to escape the tyranny of BookScan sales figures in a publishing world where disappointing sales can instantly doom an author to what is, essentially, a blacklist."Aaron Wolfe's work has appeared in Escapade, Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine and the Virginia Quarterly; fiction and poetry. He was the recipient of a North American Review writing fellowship in 1965 and one of his stories published that year appeared on the Martha Foley Roll of Honor of distinguished American short stories. INVASION, nonetheless, is his first novel and his first work of science-fiction.

"I've always loved to read science-fiction," he says, confessing to owning a "large collection" of old pulp magazines and anthologies, "and even have a passion for it. I've been addicted since I was ten and when I sit down with a science-fiction novel I'm like a child again. Who could react otherwise to this marvelous stuff?"

"INVASION gives some indication of what a literary writer of the first rank can do when he essays fiction for a wider audience. It is simply one of the most remarkable first novels, in any field, that I have ever read."

But how far should an author go in inventing a whole new persona? It is one thing to label a particular line of one's books with a pseudonym and quite another to invent a fictitious author. Or is it?

Malzberg really stresses the first novel aspect. Sure it was "Wolfe's" first novel but certainly not Koontz's. Truth or lie?

I suspect first novels tend to garner extra attention. Exciting new authors generate excitement. (More so than slowly improving authors who have been around a while) I also suspect that this "first novel" scam is currently rampant. Did you ever notice, browsing Amazon.com or looking through reviews, what a ridiculous percentage of books purport to be rookie efforts? Not to mention how many of them are, as Malzberg describes Invasion "remarkable first novels." Well of course, writers who have been publishing books for years probably can write remarkable "first" novels and reap undeserved plaudits.

Returning to the old introduction to the Dean Koontz book, I wonder about the detailed publishing history Malzberg sets out. Did Koontz actually publish all that work as Aaron Wolf or as Dean Koontz or is it a complete fabrication?

How much of the biographical material is true? Was Koontz really successful in some other artistic field? What was that? Or was that just Aaron Wolfe?

Yes, Malzberg admits that Aaron Wolfe is not the author's real name but what about his explanation for why the author wants it that way? "...compelling personal reasons that his real identity not interfere with his fiction"? Which is to say that his real identity as Dean Koontz -- a fiction writer -- would interfere with Dean Koontz' fiction?

I guess by now someone is saying, but wait, Head of Zeus is bringing out the Byzantine mysteries originally attributed to "Mary Reed and Eric Mayer" under the pseudonym M.E.Mayer. What about that?

Well, it was a big surprise to us. We knew nothing about our pseudonym until we saw the book covers. I suppose I could plead that M.E. stands for Mary and Eric. But honestly, we weren't given any explanation. I think it is because author teams, unless they are already individually famous, are difficult for readers to remember, thus, for example, there are teams identified as Ellery Queen and Charles Todd. Using both our names initially was a marketing mistake. Mary figures it was so the author name could fit on the spine.

However, it is merely a matter of branding. No one ever told us to pretend that there actually was an individual named M.E.Mayer. Head of Zeus' biographical material for M.E.Mayer makes it clear that M.E. is us.

For me it is a complicated problem. I would prefer not to have my real self attached in any way to my writing but I'm uncomfortable with the idea that the biographical information in a novel might be as much of a fiction as the book itself.

Sunday, May 5, 2013

Review: The Sweepstake Mystery by J.J. Connington

Although little remembered today, J.J. Connington, pseudonym for Alfred Walter Stewart (1880-1947), was a major writer of Golden Age Detective (GAD) fiction. A professor of chemistry, he found time to write one science fiction novel and seventeen mystery novels.

Although little remembered today, J.J. Connington, pseudonym for Alfred Walter Stewart (1880-1947), was a major writer of Golden Age Detective (GAD) fiction. A professor of chemistry, he found time to write one science fiction novel and seventeen mystery novels.

In The Sweepstake Murders a nine-man syndicate holds a winning ticket worth a quarter of a million pounds. Quite a sum, particularly in 1931, the year of publication. After one member dies in an airplane crash, court action by his estate delays the payout. The survivors agree that the prize will be shared equally by those still alive when the money is actually paid.

What could possibly go wrong?

Yes, that's right. Quicker than you can say "tontine," syndicate members begin to die in apparent accidents, starting with a tumble over the edge of a cliff at the delightfully named Hell's Gape. As syndicate members go down the value of the survivors' shares goes up. Obviously these guys should have read more mysteries before making that agreement.

Chief Constable Sir Clinton Driffield happens to be visiting the countryside, staying with one of the syndicate members, his friend Wendover -- the sort of gentleman of leisure so often featured in novels of the era. And a lucky thing too because the local police inspector while brilliant at collecting evidence is not as good as Sir Clinton at putting everything together. At least not putting it together the right way.

The suspense never lets up because the reader is kept guessing who the next victim will be. For those of us who never manage to figure out the killer, the ever dwindling number of suspects at least gives us a decent chance of making a blind guess.

The mystery becomes increasingly complicated because each new "accident" needs its own explanation. Connington belonged to the "fair play" school, which is to say he presents the reader with all the clues the detective has, all the clues necessary to solve the mystery. In a sense a novel like this is a huge puzzle. Everything the writer relates might be a clue, or a red herring.

Connington offers a huge variety of evidence for each of the multiple murders: personal entanglements, financial motives, timing sensitive alibis, physical and forensic clues, to name a few. You have to love a mystery where the solution depends on disparate clues like photographs and punctuation. Oops. I hope I didn't give anything away there. Unless you're a real mystery puzzle expert I doubt it.

And who is expert at figuring out complicated puzzles these days when practically every mystery is required to be in large part a psychological drama or thriller? Personally I think rationality is as much a part of human makeup as our underlying psychology or emotions like fear or love and therefore as worthy of being a subject of literature, even if publishers and academics disagree.

An interesting aspect of this book is that the mystery hinges in part of technology of the era, some of which was rather new in 1931. However much a novel like this might seem old fashioned, Connington was right up to date.

I happen to enjoy GAD mysteries. To me, they are much more inventive than the tiresome cookie-cutter mayhem we get too much of today (Hey, there's an idea -- The Cookie-Cutter Serial Killer!). The Sweepstake Murders is an excellent example of the Golden Age detective novel.

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

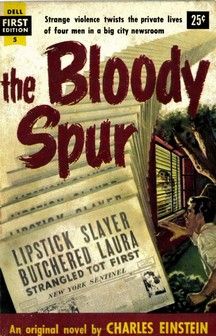

Review: The Bloody Spur by Charles Einstein

When I was following the coverage of the Boston bombing, as newspapers and television networks battled to break every new revelation first -- sometimes even trying to play detective and identify the culprits and failing miserably -- I was eerily reminded of the book I'd just finished reading, Charles Einstein's The Bloody Spur.

When I was following the coverage of the Boston bombing, as newspapers and television networks battled to break every new revelation first -- sometimes even trying to play detective and identify the culprits and failing miserably -- I was eerily reminded of the book I'd just finished reading, Charles Einstein's The Bloody Spur.

The 1953 Dell paperback original, filmed by Frtiz Lang as While the City Sleeps, isn't a western. The title's "spur" refers to a line from Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. As the blurb explains, after a serial killer has struck again....

"...in the city room of the fabulous Kyne News empire, four big-time newsmen went into action. All four knew that an exclusive beat on the killings would mean the top job at Kyne -and they were all hungry for that job. Hungry enough to buck the police, sell out their mistresses, and commit blackmail. Four decent men - corrupted by the bloody spur of ambition."

Though the story revolves around efforts to capture a serial killer, the book isn't a detective novel either. There's plenty of speculation about the identity of the psychopath but Einstein, a newspaperman and sportswriter, concentrates mostly on the newspaper drama. He throws the reader into the fog of war in a big city newsroom during a breaking story.

I found the details of the business circa 1950 fascinating in themselves, everything from how to write a headline to how to arrange print runs for different editions according to how many trucks would be available. The frenzy to beat the competition by putting a story on the wire five minutes ahead or hitting the streets with an extra in the morning rather than the afternoon, was on display, in its 21st century version, last week.

Most important, however, are the maneuverings of the high powered executives, their allies and enemies, in the battle to be appointed successor to the newly deceased executive director. As the book progresses the professional and personal entanglements become so complicated I needed to keep a character list. The newspaper men are almost as driven and tormented as the warped killer they each hope to be the first to reveal.

By the end of the book, the winner of the executive director contest won't surprise anyone who is even vaguely aware of how corporate personnel decisions are really made.

The Bloody Spur has everything covered -- the streets, the offices, the bars and bedrooms. The novel is densely written and plotted, and the characters are painfully realistic and mostly unlikeable, but it's a classic.

Thursday, April 18, 2013

Classic Novels in Twelve Words

At the Poisoned Pen Press Blog Classic Novels in Twelve Words.

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

Orphan Scrivener # 80

Ghastly home invading insects, ghastly cheeses, and even some less ghastly news about our writing, all in the newest issue of our newsletter the The Orphan Scrivener now online. Still in glorious plain text.

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

Anthologies? We Love 'Em

Towards the beginning of her fiction writing career in the eighties Mary made three short story sales to Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, straight out of the slush pile. Later we teamed up on sales to the same publication but mostly we've confined ourselves to writing the occasional short story only when asked to do so for an anthology.

In the April SPAWN (Small Publishers, Artists and Writers Network) newsletter Mary tells how our series of nine (so far) Byzantine mystery novels began with a single very short story in an anthology.

She is one a several authors who write about their experience with anthologies.

As the introduction says: "Anthologies? Are they really worth the trouble? Is there money in it for writers, or are there other benefits? How do you get in one? ...

"Many anthologies are by invitation only. Once the editors see your work in magazines or ezines or on genre sites, you may be invited to join the fun. This method saves a lot of time for editors—they'll already know your style and know you can meet a deadline. Read Mary Reed's story below and see how that first invitation grew and grew for her."

Read: Anthologies? We Love 'Em

Friday, March 29, 2013

Before Chicks Wore Minis

My memories of Easter go way back, to before chicks wore mini-skirts, back to when they gave chicks away at gas stations. Those were the days.

Easter was what you get when you substituted a magic rabbit for a magic fat guy from the North Pole and a basket of candy and some dyed hard boiled eggs for great heaps of brightly wrapped presents? That's right, a sort of second-rate Christmas. On the holiday scale Easter rated below Halloween. My trick-or-treat bag held more candy than my Easter basket and although some spoil sports gave out apples at least no one plopped any hard boiled eggs into the sack. Even the tangerines that took up so much valuable space in the Christmas stockings were preferable to eggs. What do you do with dozens of hard boiled eggs? I recall choking down egg salad sandwiches until the Fourth Of July (A holiday that barely deserved a ranking because fireworks were illegal in Pennsylvania and school was out for the summer anyway.)

I did enjoy coloring the eggs and hunting for them Easter Morning after they'd been hidden by the bunny even if it wasn't quite as thrilling as roaming dark streets in weird costumes. My family was lucky enough to have a big lawn where eggs could hide behind tree trunks, in clumps of weeds, amidst the stones in the rock garden, up in the crook of the huge maple tree in the front yard, in the corner of the sandbox, underneath a flower pot by the backdoor, up in the latticework of the rose arbor.

One early Easter it snowed. Four or five inches of heavy wet snow. My gloves were soaked through as soon as I poked around the shrubbery in front of the house. I guess the rabbit must have carried out its task in the small hours of the night because there were no tracks leading to the eggs. Those eggs were a sorry sight after they'd been hunted down and carted inside. Between sitting in the snow and my wet gloves, their colors were runny, the designs smeared. And after I'd worked so hard dipping them into the different pots of dye at various angles, blocking out patterns with a clear wax crayon. (Turned out to be good practice for the glories of tie-dye.)

The dyed eggs were left out for the Easter Bunny to retrieve and hide, you see. Which also served to prove the reality of the bunny, just as the absence of the cookies and milk set out for Santa proved that he had, indeed, visited.

There was more to the holiday than colored eggs, but not much that enthused me. I've never been fond of Easter candy. The big, candy eggs are so overly sweet they make my teeth ache and plain chocolate is...well...plain.

The fluffy chicks were more appealing. Not to eat, mind you. Although since my grandparents' chicken coop never got overcrowded, despite the traditional influx of Easter chicks....well, that's something I prefer not to think about. I suppose it taints my memory. That and pondering the fate of all those chicks they used to give away at gas stations. Sure, the ones we brought home had a coop to go too ( and never mind the chicken that showed up on my dinner plate months later. I prefer to think I was eating fowl with whom I was not acquainted, that I had not romped with in the grass.)

One year I had measles or some other childhood disease (back then there were too many to keep track of) which required me to be confined to my room for what seemed forever. I watched the adorable, baby chicks grow up in a cardboard box near my bed, which is another reason I don't recall them as fondly as I might. There's nothing uglier than an adolescent rooster, unless maybe an adolescent human male.

What Easter memories have I left out? Oh yes, the religious aspect. How you get from the crucifixion to chocolate rabbits is beyond me. Once or twice my family piled into the car and went to the drive-in where there was a sunrise service. All I remember is being half-asleep and impatient to search for eggs while the speaker in the window droned on, the words crackling and garbled. The show was longer and more boring than Lawrence of Arabia which I was also dragged to the drive-in for -- and no popcorn.

Anyway, I don't think I really believed in death at that young age, let alone resurrection. Death was just something that happened to cattle rustlers and bank robbers in television westerns. A dramatic device. I'd roll around on the ground at play, gleefully pretending to be shot dead and resurrected myself every time.

So the egg hunt was the big thing. Mysteriously, almost every year, there was an egg which eluded the hunt, only to be found weeks later, while I was mowing lawn, or weeding, a thrilling find, a faded artifact of the past nestled someplace I must have neglected to look. Best of all, you wouldn't dare use a month old egg in a sandwich. In later years I've wondered if those eggs had really been overlooked during the hunt, or saved and planted, but I never asked -- even after I figured out the Easter Bunny ruse -- and now it is too late.

Sunday, March 3, 2013

Review: Midnight by Octavus Roy Cohen

On a sleety December night taxi-driver Spike Walters picks up a fare at Union Station. The well-dressed, veiled woman instructs Walters to drive to a poorer part of town but when he arrives at the address given she has vanished from his cab, leaving her suitcase -- and a man's body. Of the missing woman Spike asks himself, as will the reader, "Where was she? How had she managed to leave the taxicab? When had the man, who now lay sprawled in the cab, entered it?"

Chief of Police Eric Leverage and amateur criminologist David Carroll cooperate in solving the crime. The departed is identified as club man Roland Warren, a cad rumoured to have been involved with a number of socially prominent married women although there has been no open scandal, and just as well being as he is engaged. It transpires every article in the suitcase belonged to him and this, along with certain other evidence, convinces the authorities and the public that Warren was planning to elope -- but not with his fiancee. Given the dead man's reputation of not being too fussy about whose wife he romances, a number of upper crust persons naturally come under suspicion, and then there's Warren's just discharged valet, not to mention the bereaved fiancee.

My verdict: Midnight features a fairly complex plot unreeled at a slower pace than in many works. Older novels of detection often display social mores that seem strange to modern eyes, for example not mentioning a woman's name at the club or the terrible consequences of cheating at cards or in some other way being touched by the rancid breath of scandal. David Carroll must navigate these treacherous waters to solve the mystery of the who and how and why of the crime.

Etext: http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/1/0/4/11043/11043.txt

Friday, March 1, 2013

Three Historicals in One Ebook

I want to alert everyone to a £4.99 ebook from Head of Zeus that contains not only One for Sorrow by Mary and me but also Bruce McBain's Roman Games and Wine of Violence by Priscilla Royal.

ROMAN GAMES: Rome, AD 95 – a city under the thrall of a tyrant. It is up to Gaius Plinius Secundus - better known to posterity as Pliny the Younger - to investigate the murder of one of emperor's favourites. He has just 15 days to solve the case, 15 days that will threaten Pliny's conscience, his life and the stability of Rome itself.

ONE FOR SORROW: Amid the splendour and the squalor of sixth-century Byzantium. A treasury official has been murdered. Could someone have killed him for a priceless holy relic? A Knight from distant Bretania seems to believe so...

WINE OF VIOLENCE: AD 1270. On a remote East Anglian coast stands the priory of Tyndal, a place dedicated to love and peace. But Eleanor of Wynethorpe, the new prioress, will find little of either... Only a day after Eleanor's arrival, a brutally mutilated monk is found dead in the cloister gardens.

That's a trip of not 500 years, not 800 years, but nearly 1,200 years and all for only £4.99.

Sunday, February 10, 2013

Review: The Rome Express by Arthur Griffiths (1907)

I must admit, so put away the big clubs, I was not too thrilled with The Rome Express. It started off in such cracking good style too, with an overnight murder on a cross continental train and six passengers and a train porter under suspicion of stabbing the victim while the express was flying along the rails.

Ahah, you cry, what an excellent set-up! And so it is.

The train arrives in Paris and the seven persons mentioned are sequestered for questioning. And who are these suspects comes the question from the back row.

Well, there's General Sir Charles Collingham and his clerical brother the Revd Silas Collingham and a couple of Frenchmen -- Anatole Lafolay, who works in the precious gem line, and commission agent Jules Devaux. Italian policeman Natale Ripaldi, the English-born Contessa di Castagneto, and Dutch porter Ludwig Groote make up the international bunch being grilled like kippers by the French authorities.

The victim is an absconding Italian banker by the name of Francis A. Quadling, and certain evidence in his compartment suggests a woman visitor. This and other clues point to the countess as the culprit, but is she the guilty party?

Alas, once the circumstances of the murder are described, they provide the reader with the necessary hint that All Is Not What It Seems although there is still a bit of sleuthing to do to find out what happened and who was involved.

My objection is that so little is made of the characters involved. To think of the motives that could be introduced to muddy the international waters! The two Frenchmen could have been defrauded by the dead man, the countess might have been blackmailed by him, perhaps he was bribing the Italian policemen and threatened to tell his superiors when he tried to arrest him on the train. The Dutch porter presents problems but then the one who appears most innocent often turns out to be the person responsible. Perhaps the absconding cad ruined the Dutchman's daughter!

I thought it a pity so much suspicion is focused on the countess that other excellent possibilities are overlooked, particularly as this is a relatively short piece of fiction and there would have been room for a subplot or two. Even so, I liked the intriguing set-up -- I wonder what Christie fans would make of it! -- so I shall probably try another Griffiths and see if I am happier with the next novel.

Etext: http://manybooks.net/titles/griffithsa1145111451-8.html

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Review: The Red Redmaynes (1922) by Eden Phillpotts

Scotland Yard Detective Mark Brendon is on holiday and while on his way to fish in an abandoned quarry on Dartmoor meets a lady whose looks strike him more than somewhat. Then a man appears, chats about fishing, and tells him about a couple building a bungalow not far from the quarry. Four days later the husband of the couple is found murdered and the finger of suspicion is pointed at his uncle-in-law, a man fitting the description of Mr Fish Chatter. And what's more, the striking lady turns out to be the murdered man's widow.

Thus begins The Red Redmaynes, the title referring to a family so-called because they all have red hair -- or should I say red manes?

The novel opens at a stately, not to say sedate, pace, but by the closing chapters the characters whirl about in a lively mazurka.

Brendon's investigative method combines "the regulation methods of criminal research with the more modern deductive system", so here we have no leaps of faith or sudden intuitions but rather stolid police work followed on reasoned lines in a case puzzling for its leads that constantly lead nowhere. For example, the trail of the red-haired uncle-in-law's mad ride on a motorbike with a suspicious sack strapped to its back vanishes into mid air -- as does the body from the bungalow.

Has Redmayne escaped abroad? Brendon suspects he may have killed himself from horror at what he did. But then another of the widow's uncles is murdered and again the body cannot be found. Brendon meantime has fallen for the widow but has a rival for her hand in the form of an Italian servant who bids fair to sweep her off her feet -- and her husband not even officially declared dead yet!

The remaining chapters rattle along with criminal goings-on all over the place including abroad, and while readers may tumble to part of the solution perhaps a quarter way through, the twist at the end is striking and the place of concealment of a certain item caught me by surprise.

My verdict: Readers may find the early part slow going but may wish to keep reading as there are surprises ahead as the pace increases and Brendon dashes hither and yon, constantly thwarted despite some near-misses. The case is finally solved with assistance from a man who sees what Brendon does not, reminding readers not all investigators are all-seeing, even those who use the modern deductive system, which depends on established facts, which are difficult to pin down in this particular case.

Etext: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14167/14167-h/14167-h.htm#2HCH0003

Saturday, January 19, 2013

When Byzantines Flew

When writing about our protagonist's adventures, our theory has always been when nothing is known from the historical record, if an event can be extrapolated from what is known and it does not violate the laws of the universe, then it is acceptable for use in our fiction.

Thus widely different sources contributed to the viability of the seemingly impossible flight of our 6th century protagonist, John the Lord Chamberlain, in Four for a Boy.

One involved an everyday autumn scene, the other two came from incidents centuries apart.

To begin with, there was the matter of watching leaves -- as surely we all do -- drifting to earth.

Then there was an illustration in Professor Barbara T. Gates' Victorian Suicide: Mad Crimes and Sad Histories, discovered in passing while researching for an as yet unsold Victorian mystery. The online text of Professor Gates' book is hosted by the Victorian Web, and in Chapter 7 she reproduces an illustration for G. W. M. Reynolds' Mysteries of the Courts of London. (1)

In this drawing, a woman has thrown herself from a window to avoid unwanted attentions. As Professor Gates notes, the woman's skirt resembles a parachute.

Similar is the tale of a 19th century suicide attempt by Sarah Ann Henley, who jumped from the Bristol suspension bridge in England. She fell over 200 feet, but was saved by the wind billowing out her crinoline, as described in a verse by one William E. Heasell reproduced on the Henly/Henley family website, which specifically mentions crinolines and a parachute descent (2)

But the most important source of inspiration was a flight that took place not far from where John took wing, albeit more than a thousand years later. According to one Turkish source, Hezarfen Ahmet Celebi, a 17th century resident of Constantinople, succeeded in gliding from the top of the Galata Tower across the Bosphorus using "eagle wings."

Sultan Murad IV, who observed the feat, richly rewarded the flyer. However, it is said the sultan, describing Celebi as "a scary man... capable of doing anything he wishes", decided "it is not right to keep such people," and so exiled him to Algeria, where he died.

We visualised Hezarfen Ahmet Celebi's wings -- and John's -- as constructed after the fashion of a modern hang-glider. Based on the sources mentioned, we felt our protagonist could fly far enough to escape his pursuers, and, although injured, that's exactly what he did.

Did readers believe us? We hope so.

(1) http://www.victorianweb.org/books/suicide/pl17.html

(2) http://www.henly.org.uk/henly/sarahhenley.html

Monday, January 14, 2013

Hogmanay: New Year in Scotland

Eric, thank you for inviting me to post on your blog, and forgive me for beginning with a cliché: travel broadens the mind. I don’t know who originated this saying, nor who added the rider, “It broadens the beam also, from too much sitting around in planes and cars.”

Sticking to the mind…travelling, which I love, can produce two quite different reactions in me. Sometimes I think (but am far too polite to say,) “Gosh, these foreigners are odd, the way they do this-or-that.” But sometimes I realise, “Heavens, we English are odd, people do this-or-that much better here.”

I’ve just come back from a lovely holiday in sunny Gran Canaria, and we were there for New Year. And heavens, we English are decidedly odd about the way we are only just now learning to appreciate New Year properly. The Spanish have a ball on New Year’s Eve, mark midnight with wonderful fireworks, and make New Year’s Day a public holiday.

Not that we English need look as far as Spain for New Year festivities. Our neighbours the Scots are world famous for their long and glorious tradition of going to town at Hogmanay and taking January 1st off to recover. Yet on our side of the border we’re only belatedly catching them up. We at least have a holiday on New Year’s Day now, a relatively recent development, and you can find good New Year’s Eve parties and midnight fireworks. But you can also still find people who – shock horror – go to bed at their normal time and sleep the night through.

I could no more sleep through New Year than fly in the air. I love the occasion, I’m excited by the whole idea of a new start, of turning over a new leaf (or should that be opening a new file in the word processor.) I haven’t a drop of Scots blood, and was born and raised in Yorkshire, but I was lucky in my childhood. I had two uncles with proper Scottish notions of Hogmanay. Uncle Whittaker loved a party and had lived and worked well north of Hadrian’s Wall, so he knew how things should be done. Uncle Harry loved a party and had the distinction of being the darkest-complexioned man for miles around. A great combination! Every New Year’s Eve they celebrated in style, and then in the wee small hours Uncle Harry went out “first footing”, visiting the houses of all his neighbours. We, the rest of the family, tagged along, even as quite young children.

As all Scots know, to bring good luck to a household, the “first foot” over its threshold in the New Year must belong to a dark man, bearing token gifts to ensure prosperity – a piece of coal and a piece of bread were what Harry brought. Once safely inside, the luck-bringer was naturally offered a “cup of kindness” for his trouble, before he went on to the next house, and the next. His capacity for “cups of kindness” was legendary.

The Ancient Romans had the right idea about Near Year; they made a big thing of it. My mysteries are set at the very end of the first century AD, in the area round York, and as my sleuth Aurelia is an innkeeper, she would certainly organise first-rate New Year parties for her friends and customers. There was a serious religious element to the occasion as well. The god Janus was one of the most important Roman deities, and he’s always pictured with two faces, one looking backwards and one forwards.

Isn’t that an excellent symbol for the start of a year? Welcome the future but don’t discard all of the past…and make sure the celebration is a good one!

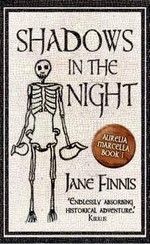

SHADOWS IN THE NIGHT was published in hardback and ebook last November by Head of Zeus for UK and the Commonwealth, and the paperback will come out this coming April. It's the first in the Aurelia Marcella series, and has already been published by Poisoned Pen Press as GET OUT OR DIE in the USA.

Website: www.janefinnis.com Blog: http://janefinnisblog.wordpress.com

Twitter: http://twitter.com/Jane_Finnis

The Aurelia Marcella Roman mysteries, published in the UK by Head of Zeus, and in the USA by Poisoned Pen Press

Tuesday, January 8, 2013

Review of One for Sorrow

Tip of the hat to Gareth for his Falcata Times review of One For Sorrow in his Historical Crime Fiction Book Combat.

"Its quirky, it has some wonderful imagination but for me the real kicker here is a lead character that more than introduces us to this world of constant danger. Back this up with wonderful pace, some great twits which when backed with an author who loves to keep you guessing, all round makes this a book that was a solid title to read."

Friday, January 4, 2013

Review: The Opal Serpent (1905) by Fergus Hume

After falling out with his boorish country gentleman father, Paul Beecot ups and goes to London to make his way as a writer. There he rents a Bloomsbury garret and while not setting the literary world ablaze manages to get along although only just this side of falling into debt. Then he finds himself caught up in evil events.

It all starts when one afternoon he happens to meet his old public schoolmate Grexon Hay in Oxford Street. Hay is turned out like the proverbial dog's dinner but condescends to share Paul's supper of plump sausages. During their conversation over the bangers, Paul talks about his beloved, Sylvia Norman, whose father Aaron runs a second-hand book shop with a bit of pawnbroking on the side, or rather in the cellar. Alas, Paul and Sylvia cannot marry until he can support a wife and they have said nothing to her father for fear he will forbid Paul to visit.

Apparently Aaron Norman has "the manner of a frightened rabbit" and seems to be always looking over his shoulder with his one good eye. Obviously something fishy is going on there, but what?

Even stranger, when he sees the titular opal, diamond, and gold brooch, Aaron faints. Shown the brooch during their dinner, Hay makes an offer for it, but Paul refuses because it is his mother's and he prefers to pawn it so he can hopefully redeem it in due course.

We now meet the memorable Deborah Junk, servant of the Norman household and devoted to Sylvia. By far the most colourful person in the novel, her unique style of conversation would not disgrace a working class character created by Dickens, and when she is on-stage she dominates the scene.

But there's plenty going on when she's engaged elsewhere. Why did Aaron Norman faint when he saw the serpent brooch? Who is the man who warns Beecot against Hay, describing the latter as "a man on the market", and what does the curious phrase mean? Why did an Indian visitor to Aaron Norman's book emporium leave a pile of sugar on the counter? Does a truly ghastly guttersnipe born to hang know more than he lets on?

My verdict: The Opal Serpent contains some surprisingly strong content, such as certain comments made by the murderer, which would be disturbing even in this day and age, while the method used to kill the victim in full view of others is so awful I was surprised to find it in a novel of this vintage. Plus the use to which the brooch is put is equally grim.

This novel trots along at a steady pace with as many twists and turns as a serpent as it slithers its way to a rip-roaring denouement, and I must say the plot certainly underlines the traditional belief opals are unlucky! Recommended.

Etext: The Opal Serpent